An Outsider’s View By Sarah Thornton

Originally published December 24, 2018 on Art Jewelry Forum

(April Higashi, owner of Shibumi Gallery, is featured in this article)

I recently encountered a fascinating subculture, populated mostly by women who make, buy, and sell small objects in a vast range of materials that they sometimes install on their bodies. Called contemporary jewelry or art jewelry (and sometimes artist jewelry), this field has a distinct set of etiquettes and values that makes its wares more thought-provoking, but no less theatrical, than costume jewelry. While many practitioners call themselves “artists,” they shirk the label “sculptor” and, despite its technical accuracy, “wearable sculpture” is rejected for its pretension and insufficient pride in the field’s ornamental origins. To an outsider, this refusal of more “serious” nomenclature is curious. It’s particularly noteworthy when paired with persuasive assertions about the field’s status as art. “Going back into pre-history, the first piece of sculpture was likely jewelry,” says Rebekah Frank, a practitioner who works principally in steel, and the former director of Art Jewelry Forum. “Jewelry has a long history of exuding power and offering protection.”

As someone who studied art history as an undergraduate, earned a PhD in the sociology of culture, and has been writing about the art world for 20 years, I think art jewelry has a leg up on regular old art in at least six important ways.

1. You can touch it! In an increasingly digital world where experiences that once offered a tactile dimension (like reading, shopping, and dating) are being performed online through small screens, art engages the whole body with real texture and scale. Here, art jewelry delivers more, such as the sensation of cold metal, rough stone, and smooth plastic. Indeed, it is a profound pleasure to close overused eyes and literally feel an idea.

2. The body—rather than an inert white wall or dull gray plinth—is the work’s primary platform. “The wearer is your pedestal out in the world and your spokesperson. Often they are better at it than you,” says Emiko Oye, an art jeweler who makes elaborate statements with Lego bricks. She constructs her work on four mannequins named Julian, Lola, Lolita, and Martha, the last of which is named for her grandmother, who used it to make her own clothes. Others execute their work on themselves. “I wear it while I am making it—testing how it lies, adjusting how it hangs. A major part of my process is trying it on,” says Nikki Couppee, an artist best known for her nostalgically feminine Pop assemblages of pink Plexiglas and shells. “Once it’s finished, though, I never wear my own work. It feels uncomfortably self-promoting. But I love to trade and wear other people’s work and see them wear mine.”

3. Art jewelry offers greater opportunities for social interaction. A few years ago, the National Endowment for the Arts did a study of why people attend art institutions. The number one reason offered was to socialize with friends or family. Significant art jewelry is invariably a conversation piece, so it invites engagement with others, and inserts the wearer into the classic interpretative dyad between artist and viewer. From this point of view, the essential habitat of art jewelry is not the exhibition, but the cocktail party. I admire the honesty and transparency of this situation. In the opaque art world, the premiere event is an alcohol-lubricated social gathering between 6 p.m. and 8 p.m., whose alibi is an exhibition opening.

4. If contemporary art is about spreading startling ideas and opening people’s minds, then why not capitalize on our basic human desire to adorn ourselves and carry talismans? “It’s not about wearing big jewelry. It’s about challenging expectations and telling stories,” declares Mike Holmes, a dealer who ran Velvet da Vinci for 26 years and now curates exhibitions and pop-up stores. “Think of a grandmother’s wedding ring, passed down. Or a political button. Or a war medal, for that matter. These objects give concepts a powerful social life.”

5. The relatively small size and lower overheads of art jewelry enable greater experimentation. “My interest in jewelry doesn’t come from a love of adorning myself,” says Julia Turner, an artist whose oeuvre includes necklaces made out of oiled walnut and brightly stained maple. “I like jewelry because the scale works for me. I enjoy setting up problems and looking at them from a million points of view. With jewelry, the iterations can be very fast.”

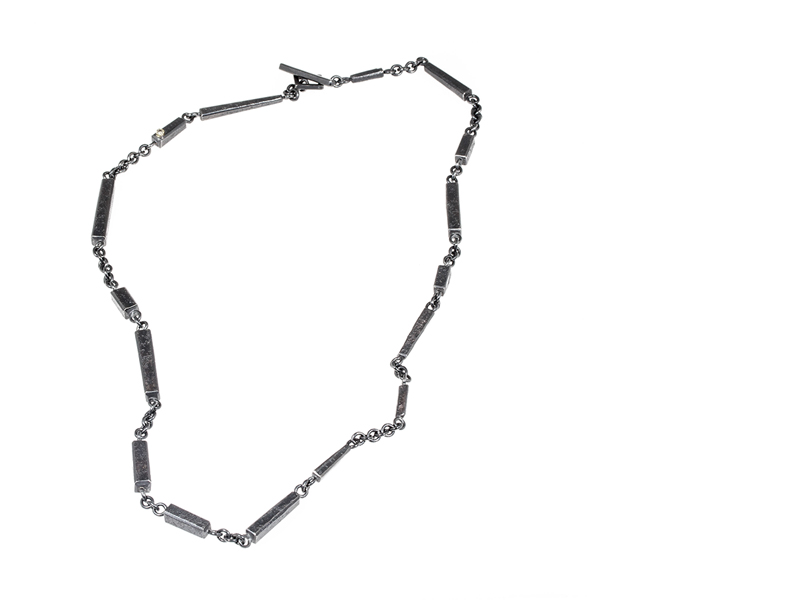

6. Jewelry artists’ concern for materials is admirably focused and investigative. Its proximity to fine jewelry means that its exploration of the dignity of nonprecious materials often leads to a quiet critique of bling, wealth, and class. “You can’t avoid the history of perceived value, so it is fun to play with preciousness as a theme,” explains Raïssa Bump, a jeweler who often creates knits and quilt patterns in silver. “I like my pieces to shift the wearer in some way, giving them a statement that can be integrated into their self-expression.”

Strengths often lead to weaknesses. Indeed, much contemporary jewelry is so obsessed with materials that the theme crowds out other artistic concerns and leads to works trapped in a conversation with craft. Moreover, in regions like the San Francisco Bay Area, the hippie legacy looms large and, along with it, a predilection for natural materials and a resistance to new technologies that also ushers work back into the craft ghetto.

Ironically, the one term from which my interviewees appear most anxious for distance is craft, which they associate with a lack of aspiration and old-lady amateurism. Perhaps craft’s theoretical antagonism to the contemporary is to blame? “The old craft world is dying and being reborn within the design world,” explains Susan Cummins, one of America’s foremost collectors of art jewelry. “Due to its functionality and materiality, jewelry belongs under the rubric of design.”

During my studio visits, in which I was generally scintillated, I nonetheless experienced a few disappointments. Given that the body is the main stage of the work, I was initially shocked by the number of practitioners who told me that they “don’t think” about gender and perceive their work as innocently gender-neutral. It then became clear that the women practitioners I was interviewing were making work for women—a fact that was so obvious that it had sunk beneath their cognizance. For example, after saying that she didn’t think about gender, one respondent mused: “The male torso is a nice platform. It would be nice not to think about boobs.”

Clearly, an important challenge for the status of the field is to gain an audience among men. April Higashi, a jeweler who is also the owner of Berkeley’s Shibumi Gallery, one of two art jewelry stores in the Bay Area (the other is De Novo in Palo Alto), says that, outside of wedding rings, only 3% of the pieces she sells are worn by men. “It is hard to get men to even try it on and, if they do, they can’t wait to take it off,” she explains. When she recently did a show of chunkier jewelry for men, the works sold mostly to women.

To expand the audience for and stature of contemporary jewelry, I think advocates should consider renaming the field. It’s unlikely that the term “jewelry” will cease (anytime soon) to be associated with thoughtless adornment, commercialism, superficiality, and femininity. I’m a lifelong feminist and believe in the battle to elevate the feminine but, for me, “jewelry” is irretrievable, particularly as its cultural associations are dominated by fine jewelry.

I think it’s worth considering the truly gender-neutral and resolutely contemporary term “wearables.” Now that people of all sexes are wearing computers on their wrists and headphones around their neck, adoption of the term could help put the small objects, formerly known as art jewelry, into conversations with a more ambitious set of themes. Although the term “wearable” is being used by the tech sphere, it’s not owned by it. It isn’t too late!

Wearability is a weird and wonderful concept. Many of my interviewees made sense of it by evoking a woman wearing four-inch heels. Of course, the physicality of the work will always be central, but what if the issue of wearability took a more intellectual turn? What if the first question were: Does she have the energy to put on this piece and talk about it all night? Or, does this object align with his political values and project a better future? As a category, “wearable art” is not pretentious, prissy, trivial, or trinket-like. Most importantly, it’s not oxymoronic. With commanding matter-of-factness and self-respect, it says what it is.

Sarah Thornton is an ethnographer, writer, and public speaker. Formerly the chief writer on contemporary art for The Economist and, before that, a brand planner in an advertising agency, Thornton has a BA in art history and a PhD in the sociology of culture. She’s the author of three books: Seven Days in the Art World, 33 Artists in 3 Acts and Club Cultures: Music, Media and Subcultural Capital. She has lived most of her adult life in London, England, but now resides in San Francisco, CA. For more information, see: www.sarah-thornton.com. Photo: Margo Moritz