04/07/2016

Shibumi Gallery, Berkeley, California, USA

By Jessica Hughes

Originally Published On Art Jewelry Forum

Christina Odegard’s deep appreciation for the beauty and elegance of natural materials, as well as her extensive exploration of form, is apparent in her work. Meanwhile, “shibumi” is a Japanese word referring to a particular aesthetic of simple, subtle, and unobtrusive beauty. So it’s no surprise to see Christina Odegard’s work featured at the Shibumi Gallery in Berkeley, California.

Jessica Hughes: Can you tell us about your background?

Christina Odegard: I grew up in a rural community in England, about halfway between London and Brighton on the southeast coast, although both my parents are American. I spent many a day roaming our family farm, exploring nature. I attended an alternative school, which taught many traditional crafts, fostering my love of the arts.

I’ve read that you came from a family of artists. What made you decide to go into the jewelry field?

Christina Odegard: I attended Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), thinking I would continue studying fashion design, as I had been working in costumes and fashion. After a foundation year, I had to decide my major, and new experiences led me to the jewelry and light metals department.

Can you talk a little bit about your process and what inspires you?

Christina Odegard: I’m very interested in the work, lives, and processes of many artists. Artworks from ancient to contemporary inspire me, but my inspiration also comes from the process of transforming natural raw materials. Working with these diverse materials informs a direction to create a form which is quiet and elegant, yet maintains a simplicity of its origin.

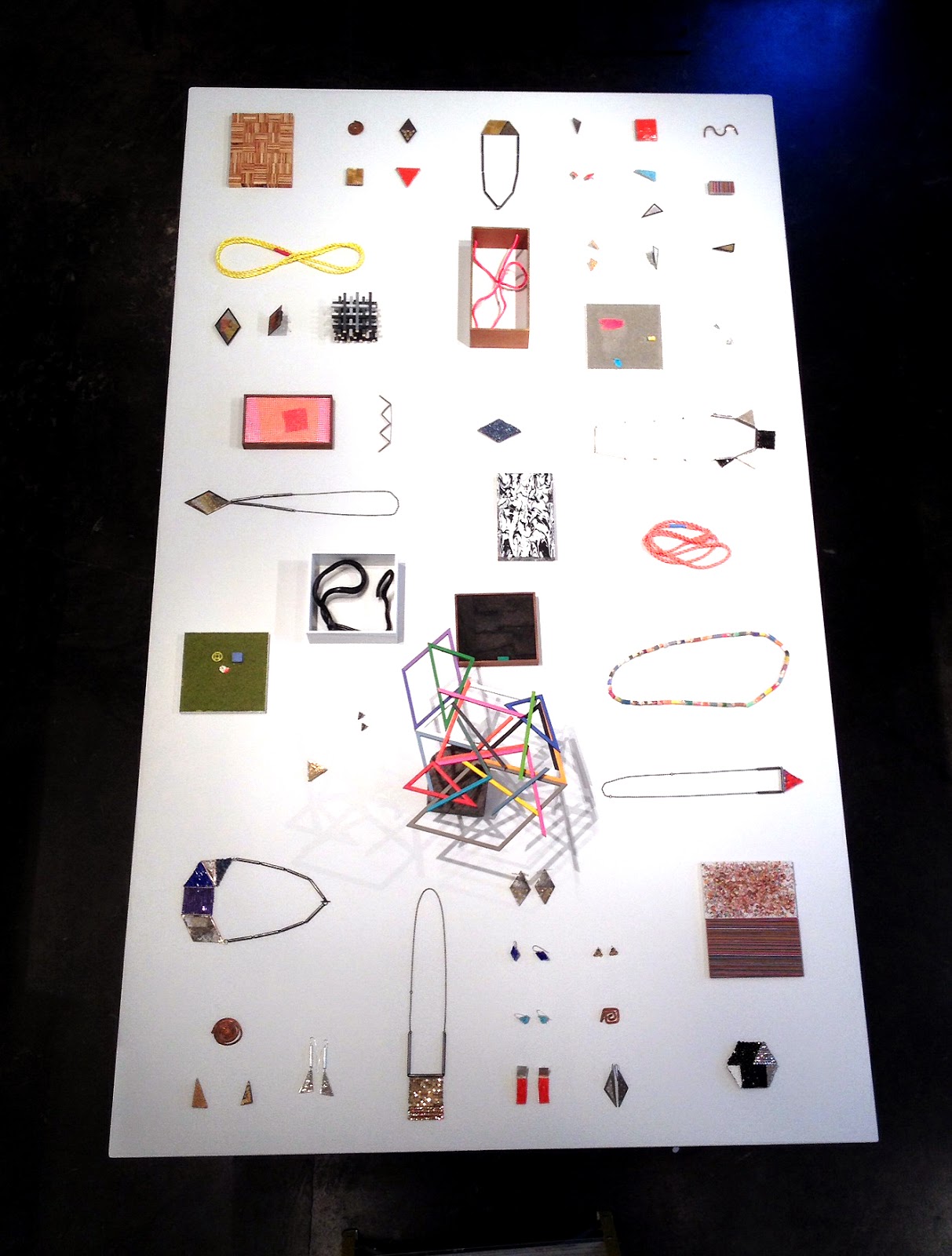

Your show at Shibumi Gallery is open from March 12 through May 1. Can you tell us about the pieces you’re presenting there?

Christina Odegard: For this show I was interested in using black as a unifying theme. A few summers ago, my husband, daughter, and I spent some weeks traveling through Iceland. There, inspired by the dramatic lunar landscape, I picked up some obsidian, adding to a growing collection of black material. These blacks are all so diverse, yet subtle and quiet. For this show I have also included black diamonds, jet, ebony, horn, coral, and tourmaline, exploring further subtleties of the shade.

You’ve been carving or casting a similar shape—the cluster—in a variety of materials (jet, horn, tourmaline, gold). What dictates the use of one material over another in each of these instances?

Christina Odegard: The cluster form is a fascinating form to carve, as from all angles it can look different. After each cluster I carve, I still feel there is more to discover; I can refine it, perfect it, explore deeper. Thus it’s interesting for me to carve the cluster in different materials, to see how each responds. It’s like a question that never gets answered, but it’s still fascinating to ask it again and again.

Proposing variants on the same theme suggests an interest in developing design solutions into ranges (I am thinking for example of the tourmaline, the gold, and the pavé version of your Cloud ring). Contemporary jewelers tend to be timid about producing work across materials, preferring the art logic of developing various works using the same material and process. Does that make you a “designer”?

Christina Odegard: I’m not really concerned about labels. When I’m interested in a form or idea, I will pursue it until it no longer holds a mystery for me. Using different materials is an exploration, and can push me technically and artistically.

Among these materials, bison horn is unusual. The power and malleability of that material is particularly apparent in your Bison d’Or earrings. How did you begin working with it, and why do you like it?

Christina Odegard: Horn is very malleable, and it can be cut and carved in so many ways. It’s also a material used in ancient/primitive jewelry, which interests me.

You’re a jeweler and a sculptor. Do you approach creating jewelry differently than sculpture?

Christina Odegard: The jewelry and sculpture differ primarily in size. I approach them similarly, although for me the jewelry has to work on the body, complement the beauty of the wearer, and not dominate or take over. Sculpture can stand alone, responding to its surroundings, but not limited by them. I have created a series of sculptural bronze pieces, which is a material I haven’t used in jewelry.

With your husband, you founded the gallery called Matin in Los Angeles. Does being a gallerist affect the way you make jewelry? Does being a jeweler affect the way you choose art and artists for the gallery?

Christina Odegard: My husband, Robert Odegard, is the primary gallerist for Matin. We are interested in a particular aesthetic, quality and beauty. This is what informs our goals for the gallery.

From the perspective of an artist and a gallerist, do you have advice for emerging artists?

Christina Odegard: Work hard and be authentic.

What projects are next for you?

Christina Odegard: I’m creating a new series of small cluster sculptures, larger than the jewelry pieces yet using some of the same materials.

Have you seen, heard, or read anything interesting lately that you could share with us?

Christina Odegard: One artist/writer I truly admire is Edmund de Waal. I highly recommend his most recent book, The White Road.

Thank you!

The works in this exhibition are priced between US$200 and $12,000.

Jessica Hughes is a graphic designer, writer, and jewelry enthusiast. Based in Providence, Rhode Island, Jessica received her BFA at Tyler School of Art, Temple University, Philadelphia. Currently, she is the senior visual design manager at a fashion jewelry company, where she focuses on graphic design, jewelry design, marketing, and trend research.